A dispute over $15,000 could reshape the US tax code and potentially freeze $340 billion in government revenue.

On December 5, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments Moore v. United Statesa case centered on the mandatory repatriation tax (MRT) included in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. The thought of a $14,729 tax bill may fill some taxpayers with dread, but advocates say the outcome of this hearing will could have a much more costly impact on both the tax rules already in place and those being considered by President Joe Biden’s administration.

Dont miss

Here’s why this case is so pivotal.

Reform of the tax code

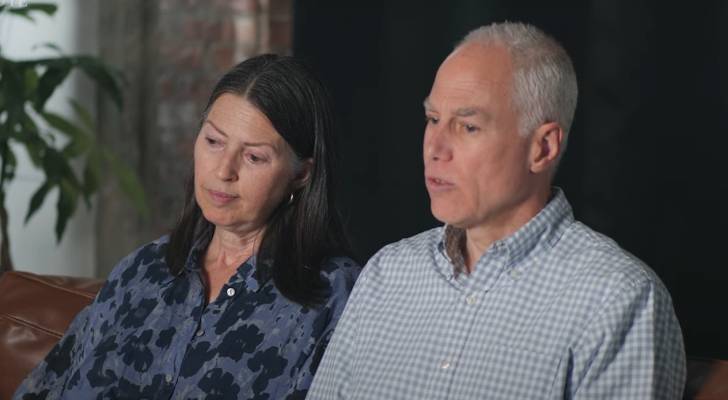

Charles and Kathleen Moore of Redmond, Washington State, are the plaintiffs in this case. In 2005, the couple invested $40,000 to buy a 13% stake in KisanKraft, an India-based manufacturing company. However, when Congress passed President Donald Trump’s signature Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), it imposed a levy on US taxpayers who owned more than 10% of a foreign corporation.

The government expected the rule to generate nearly $340 billion in tax revenue over 10 years.

Under this new rule, the Moores paid $14,729 in taxes, despite telling the American Enterprise Institute, a center-right thinktank, that they hadn’t taken a dime from the business at the time. They are now seeking a refund, arguing that the tax is “unconstitutional” and “a non-apportionable direct tax that violates the apportionment requirements of the Constitution.” Simply put, the couple believes that the government has no right to tax unrealized profits.

A gain is not income unless and until it is realized by the taxpayer,” attorney Andrew Grossman According to reports he told the Supreme Court justices during the hearing.

If the Supreme Court rules in their favor, it could open the door to overhauling the nation’s tax code. Stan Veuger, Alex Brill and Kyle Pomerleau, senior fellows at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), worry that if the Moores win, it “risks upending key elements of the current federal income tax and wreaking havoc on parts of the American economy.”

One of their main concerns is that requiring income to be realized before it is taxed could lead to increased “economic distortions, create policy uncertainty and reduce federal revenues.” Calling it “economically incoherent,” the AEI fellows add that a ruling in favor of the Moores could lead to reintroducing problems that the previous legislation sought to address and thereby increase wealth inequality as the wealthy strategically hold onto their assets and they look for buying or selling opportunities that allow them to avoid paying taxes.

Other experts are also concerned about the impact on public revenues. Tax Policy Center Fellow Eric Toder calculates that the federal government could lose $87 billion in revenue for 2024 and $125 billion through 2028 if the court rules in favor of the pair. To cover the shortfall, Congress may have to enact new rules. If the shortfall is not covered, it could further widen the government’s budget deficit.

Meanwhile, Democrats worry the case could affect their ability to implement an estate tax.

Read more: Owning real estate for passive income is one of the biggest myths in investing — but here it is how you can actually make it work

Undermining the wealth tax

In late November, lawmakers was introduced the Billionaires Income Tax Act — a new rule they say could close loopholes and force wealthy individuals to “pay their fair share” of taxes.

The bill would tax anyone with more than $1 billion in assets — or $100 million in income for three consecutive years — at 20 percent. This will apply to both realized income and unrealized profits. The proposed legislation is co-sponsored by 15 Democratic Senators and over 100 supporting organizations.

Democratic Sen. Ron Wyden, who is championing the Billionaires Income Tax Act, argues that the bill could be stalled if the Moores win their case. That would jeopardize a key element of the Biden administration’s tax agenda.

Based on their feedback, this shows up that some Supreme Court justices are leaning toward a narrow ruling to avoid far-reaching effects on the tax code and the economy. However, a decision is not expected until 2024.

What to read next

This article provides information only and should not be construed as advice. Provided without warranty of any kind.