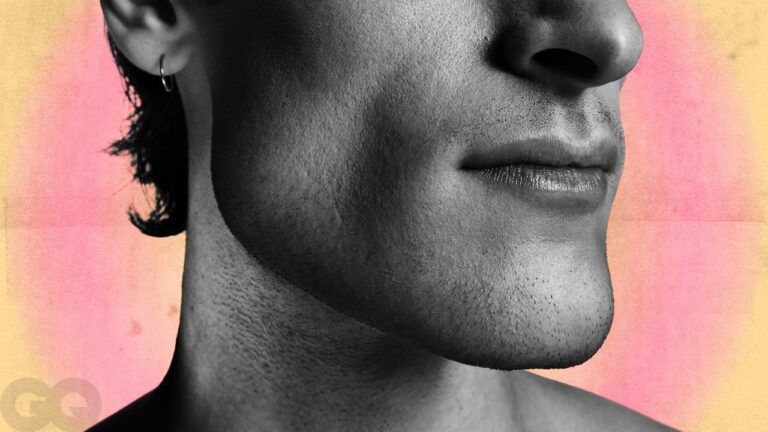

Six hours later signing the papers, Ali walked out of Rome’s operating room. He regained consciousness and felt surprisingly energetic, but was unable to walk, use the toilet, or eat. He shares some photos of himself post-surgery, his swollen face wrapped in bandages. A mop of messy hair. Dark blood around his nose. He also shares some of his “before” photos, portraits he’s used for his dating profile. He is well-groomed, wearing one patterned shirt, impressive poses in a park. He seems sweet, serious, if a little uncomfortable in his own skin. It’s a vulnerable confrontation.

Ali spent that first day calling his friends and family, then was discharged to recuperate for a few more days at his Airbnb. There, he told me, he spent time looking in the mirror. Seeing his swollen face wrapped in bandages staring at him, he began to feel his anxiety rising. “I took a big bet,” he says. “I started to struggle mentally, thinking, ‘What have I done? I’ve broken my whole face to look better and I don’t even look better now.” All he could do, he said, was drink fluids and wait for the swelling to go down.

Love and its pursuit, it never felt more like a market. On dating apps from Tinder to Feeld and even more everyday social media, we think of ourselves as brands, vying for investment from potential matches. “You have almost infinite options,” says Ruth Holliday, professor of gender and culture at the University of Leeds. “Then, at the same time, everyone is trying to maximize their own potential.”

“And some men are just turned off by it,” she continues. “They fall off the bottom because they don’t have a good job or a stable income. They’re not particularly good-looking, and then they withdraw and become abnormal and get angry with women on the fringes.”

Red pill and black pill ideologies can tap into this discontent, fan it and drive people to despair. For those who identify as “incels” (the term originally meant “involuntary celibate”), the black pill is a particularly nihilistic truth to swallow. It can lead to suicidal ideation, violence and even acts of terrorism: in 2014, a gunman killed six students at the University of California before killing himself after posting about his inability to form a relationship and calling for further violence against women. The call was answered by another gunman, who killed 10 people in Toronto in 2018. In 2021, a self-identified soldier killed five people in Plymouth. Adherence to a vision of manhood that leads some men to choose jaw surgery may lead others to hatred.

Monosphere communities are often rooted in loneliness, insecurity and a sense of disempowerment. It’s the same anxiety that’s driving record numbers of men to pay for hair transplants, botox and even leg lengthening surgeries. the desire to look healthy, youthful, competitive. Prejudice based on appearance is real (though arguably felt more acutely in the form of racism or by people with disabilities or disfigurements). But even Daniel Hamermesh, an economist who quantified this effect in his book, Beauty pays, concluded that investments in appearance, whether through surgery, fashion, or cosmetics, usually had limited returns. “Bad appearance,” he wrote, “is not a critical handicap, nor something which our own actions cannot at least partially overcome, nor something whose weight should be so overwhelming as to crush our spirit.” Like Kjerstin Gruys, its author Mirror, Mirror from the wallsaid, while those at the ends of the beauty scale may have very different experiences in life, most of us are (unfortunately… or fortunately) pretty average.