Imagine examining a dog or cat’s mouth and spotting a broken tooth. The pet seems to be eating just fine, with no apparent discomfort. Should you keep your findings quiet, share your thoughts, recommend extraction or refer for vital pulp or root canal treatment? Let’s dive deeper into the world of broken teeth in our patients.

Dental accidents happen

Our patients experience dental mishaps from accidents, fights, chewing on hard toys, deer antlers and falls. Sometimes these incidents can lead to fractures in their teeth. Maxillary and mandibular canines are usually the teeth most prone to fracture, followed by maxillary incisors and fourth premolars.

Cats and dogs have different tooth structure. In cats, the pulp chamber extends within millimeters below the coronal tip, while there is usually considerable protective dentin beneath the enamel in mature dogs. When the wound exposes the pulp, oral bacteria invade, causing infections that often spread to the surrounding tissues and bones.

Figure 1: Periapical elucidation consistent with periapical periodontitis affecting the right mandibular canine. Extraction or root canal treatment is indicated.

Figure 2a: Discolored maxillary left first incisor.

Figure 2b: Radiograph shows an enlarged root canal compared to adjacent teeth consistent with a non-vital treatment or tooth root canal extraction.

To get a better picture, intraoral dental x-rays are helpful. they help identify pulpal and periapical problems and can assess the width of the root canal compared to the contralateral tooth (assuming it is still vital). A non-vital tooth may have a wider root canal, indicating previous pulp damage and necrosis (Figures 1, 2aand 2b).

The many faces of broken teeth

The presentation about teeth with endodontic pathology (subjects in

the tooth) may vary. Brain trauma can lead to pulpitis in some cases, without an obvious fracture. Internal pulp bleeding is often noticeable as a discolored tooth (Figure 3). Sometimes you will see a broken crown without pulp exposure (uncomplicated crown fracture), while other times, the pulp may be exposed (complicated fracture). In advanced scenarios, you may even find fistulous tracts below the gum line (Figures 4a and 4b).

Figure 3: Discolored left canine maxilla secondary to pulpitis.

Figure 4a: Fistula apical to the mucosal line secondary to apical periodontitis in the damaged maxillary left canine.

Figure 4b: 3-D CBCT confirming marked periapical bone loss.

Most pets with broken teeth show no signs of discomfort, even though they feel pain just like humans. Cats, especially, are experts at hiding their pain. However, there are signs such as occasional chewing on one side, excessive salivation, or avoiding hard food or treats. (Table 1)

The treatment dilemma: To rescue or to extract?

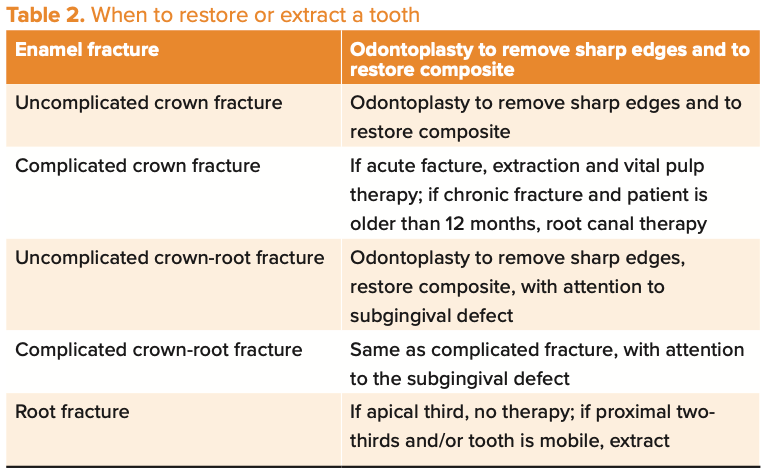

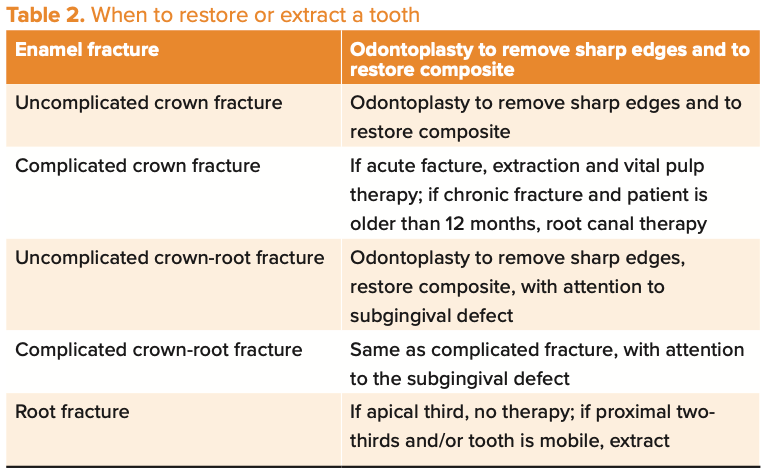

What should you do when dealing with a broken tooth that exposes the pulp? (Table 2) Well, you have 2 main options:

1. Tooth Extraction: Complete removal of the damaged tooth, which stops the pain, but can affect oral function.

2. Endodontic treatment: This approach aims to save the tooth and restore its function, and includes root canal therapy and vital pulp therapy.

Factors that influence your decision

Figure 5: Right maxillary fourth premolar fracture affected with advanced periodontal disease, extraction indicated.

Several factors come into play when deciding between extraction and endodontic treatment.

1. Severity of tooth damage: If the fracture is limited to the enamel or involves dentin in a mature dog, without exposing the pulp, often no further treatment is required if probing and intraoral radiographs show no evidence of periodontal disease. Action is required for an uncomplicated crown fracture if the animal is young (with a large pulp chamber and root canal) and when the pulp is exposed (complicated crown fracture).

2. Periapical and periodontal changes: Supporting the teeth is vital to successful endodontic treatment. Prognosis may be poor if moderate to advanced periodontal disease is present. In these cases, extraction is the treatment of choice (Figure 5).

3. Function of teeth: Although any tooth can be treated endodontically, certain teeth are more critical to oral function, including canines and maxillary fourth premolars. Saving these is a priority (Figures 6a and 6b).

Figure 6a: Complicated canine left maxilla.

Figure 6b: Root canal radiograph.

4. Owner Expectations: Recent veterinary literature reports that root canal therapy has a high (94%) long-term success rate. Make sure your pet’s caregivers understand the prognosis, cost, and aftercare involved in endodontic treatment.1

5. Your experience and comfort: If you are uncomfortable with advanced endodontic procedures or if the client refuses them (referral), extraction may be the only option for pulp-exposed teeth.

Vital pulp therapy: lifesavers for some teeth

Vital pulp therapy includes partial coronary pulpectomy, immediate pulp capping, and reconstruction. This approach works well for teeth that have experienced acute (less than 48 hours) pulp exposure. can save tooth function without the need for root canal treatment. (Figures 7a and 7b).

Figure 7a: Acute complex crown fracture of the left maxillary canine.

Figure 7b: Medicine placed over the exposed pulp prior to crown restoration.

Age also plays a role

The age of the patient and the time of the fracture can also influence the choice of treatment. Young patients with open root apices may benefit from procedures such as vital pulp therapy, while older patients with closed root apices can undergo standard root canal treatment.

Broken teeth in our pets are common and require careful attention. Whether it is tooth extraction or endodontic treatment, your decision should take into account the severity of the lesion, periapical and periodontal changes, the function of the tooth, the owner’s expectations and your expertise. Intraoral dental radiographs are essential for informed decision making. Managing broken teeth relieves pain and ensures the long-term oral health and happiness of your furry patients.

Report

Kuntsi-Vaattovaara H, Verstraete FJ, Kass PH. Results of root canal treatment in dogs: 127 cases (1995-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002;220(6):775-780. doi:10.2460/javma.2002.220.775

Jan Bellows, DVM, DAVDC, DABVP, FAVD, received his undergraduate education at the University of Florida and his doctorate of veterinary medicine from Auburn University. After completing his internship at the Animal Medical Center in New York, New York, he returned to Florida, where he practices companion animal surgery and dentistry at All Pets Dental in Weston. He has been certified by the American Board of Veterinary Practitioners (canine and feline) since 1986 and the American Veterinary Dental College (AVDC) since 1990. He was president of AVDC from 2012 to 2014 and is currently president of the Foundation for Veterinary Dentistry.