When to export

Extractions are indicated when there is stage IV periodontal disease (the tooth has more than 50% loss of support based on probing depths, greater than stage III mobility, exposure to stage III hair loss, or when gingival recession has progressed beyond from the gum line). Extraction is also the best treatment for stage III periodontal disease, where the tooth has 25% to 50% loss of support and the owner or patient will not allow proper home care.

Some fractured teeth are best extracted, especially those with pulp exposure and stage III or IV periodontal disease, severe internal resorption, or when root canal treatment is impossible due to owner wishes or practice capacity and lack of referral option.

Extractions are also indicated for the treatment of tooth resorptions exposed in the oral cavity. In addition, cats affected by chronic feline stomatitis can be helped through the extraction of selective teeth or all teeth.

Supernumerary teeth that cause crowding, predisposing the teeth to periodontal disease, must be extracted. In addition, persistent baby teeth should be removed as soon as possible at the time of diagnosis to avoid potentially harmful malposition of adult teeth.

Complications from routine exports

Consider why export complications occasionally occur:

- Excessive stress at the crown/root interface leads to root fracture.

- Excessive bleeding due to inadvertent severing of neurovascular bundles occurs during removal of the buccal alveolus, creating improved exposure.

- Mandibular separations are caused by excessive pressure on bone weakened by apical periodontitis.

Fortunately, these complications can be mitigated by first performing areolar amputations.

Functional technique

- Administer local anesthesia.

- Insert the scalpel blade into the gingival sulcus and advance it apically 360 degrees to cut the coronal periodontal ligament.

- Create a full-thickness oral mucoperiosteal envelope or pedicle flap, including the superficial mucosa, submucosa, and periosteum.

- Use a #701 surgical tapered transverse slot to create a bone gutter on top of the cementoenamel junction.

- Place the visor horizontally at the cement-enamel junction to remove the crown.

Surgical bur #701 used to groove the crown of the right mandibular first molar.

6. Gently lift the crown from the roots using extraction forceps.

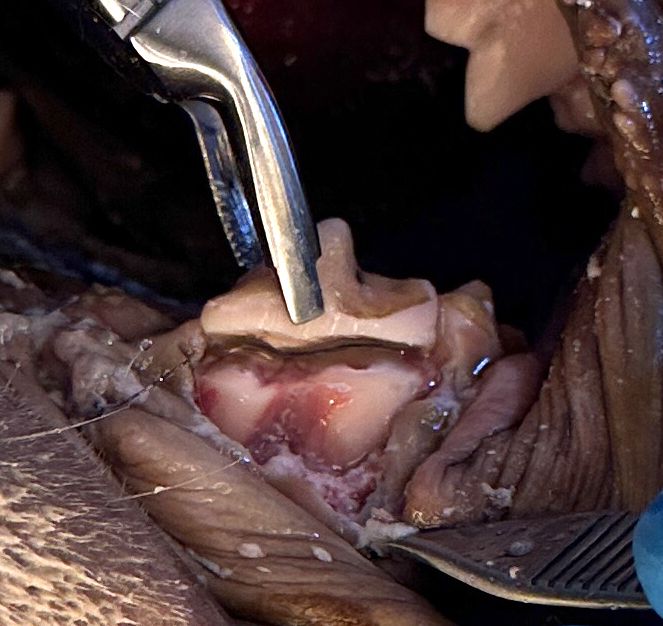

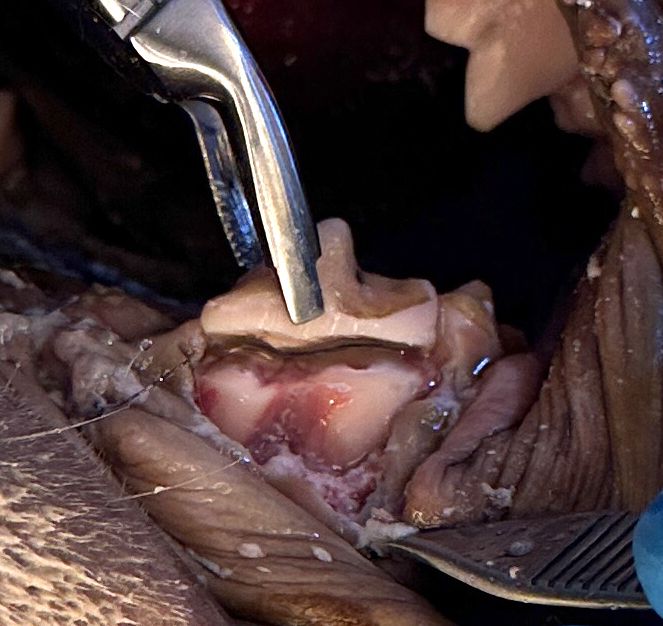

Rongeurs used to lift the fourth premolar of the right maxilla from the underlying roots in a cadaver specimen.

7. Use the #701 Surgical Tapered Transverse Slit to create a trench around the root(s) to facilitate insertion of the sharpened wing tip elevator blade.

Figure A: The maxillary fourth premolar in a cadaver specimen exposing the roots after crown removal.

Figure B: The appearance of the roots of the mandibular first molar after amputation of the crown.

Figure C: Surgical bur #701 used to create trenches around canine roots in a cadaver specimen.

Figure D: Surgical bur #701 used to create a trench around the maxillary fourth premolar in a cadaver specimen.

8. Remove enough buccal alveolar bone to expose the root surface.

Figure A: A #701S crown used to remove the buccal alveolar bone overlying the roots of the mandibular first molar.

Figure B: Creating a trench for easy insertion of the maxillary canine wingtip into a cadaver specimen.

9. Apply moderate torque with an appropriately sized wingtip elevator circumferentially until vigorous root mobility is established.

A wing-tip elevator placed in the trench to facilitate extraction of the canine root in a cadaver specimen.

10. Remove the roots with a toothpick or fine extraction forceps.

The delivery of the maxillary canine root is shown.

11. Clean the sharp alveolar apex with the football diamond bur before suturing.

12. Enlarge flap if necessary to facilitate tension-free closure.

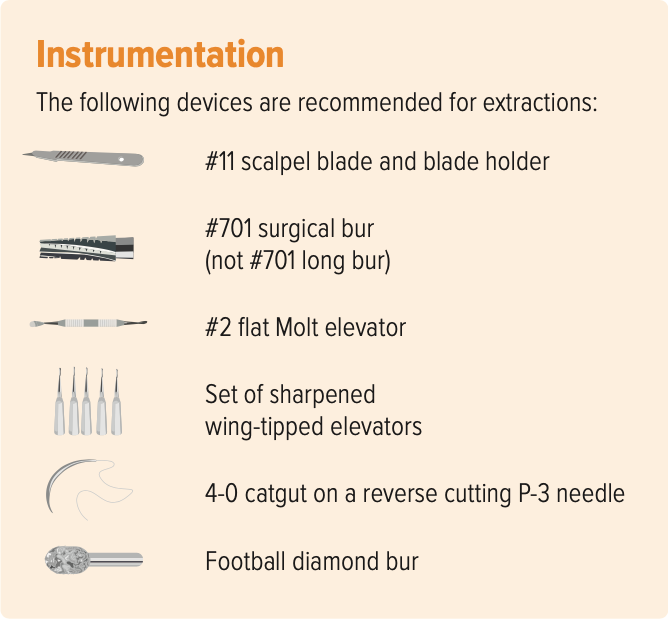

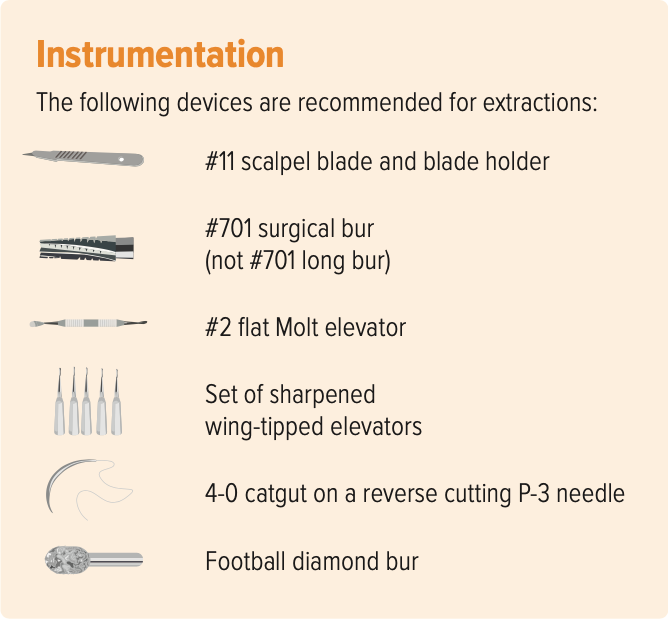

Package key

Removing the crown as part of the export process is a win for everyone. It reduces the size of the flap required to access the buccal alveolus, allows excellent visualization of the roots, reduces bleeding from inadvertent sectioning of the arterial supply, and reduces extraction root fracture and stress.

Elegance is a good thing.

Jan Bellows, DVM, DAVDC, DABVP, FAVD, received his undergraduate education at the University of Florida and his doctorate of veterinary medicine from Auburn University. After completing his internship at the Animal Medical Center in New York, New York, he returned to Florida, where he practices companion animal surgery and dentistry at All Pets Dental in Weston. He has been certified by the American Board of Veterinary Practitioners (canine and feline) since 1986 and the American Veterinary Dental College (AVDC) since 1990. He was president of AVDC from 2012 to 2014 and is president of the Foundation for Veterinary Dentistry.