In the town of Sitka, Alaska, local Native Americans take small boats and planes to spend a week fitting brand new dentures at a clinic staffed by UConn School of Dentistry faculty and residents.

Since 1997, Dr. Thomas Taylor, professor and chair of prosthetics, and Dr. John Agar, professor of prosthodontics—along with a growing number of third-year prosthodontic residents—travel to Sitka nearly every June to provide new smiles to a population that might otherwise never be able to. receive appropriate dental care. Over 800 dentures have been manufactured to date.

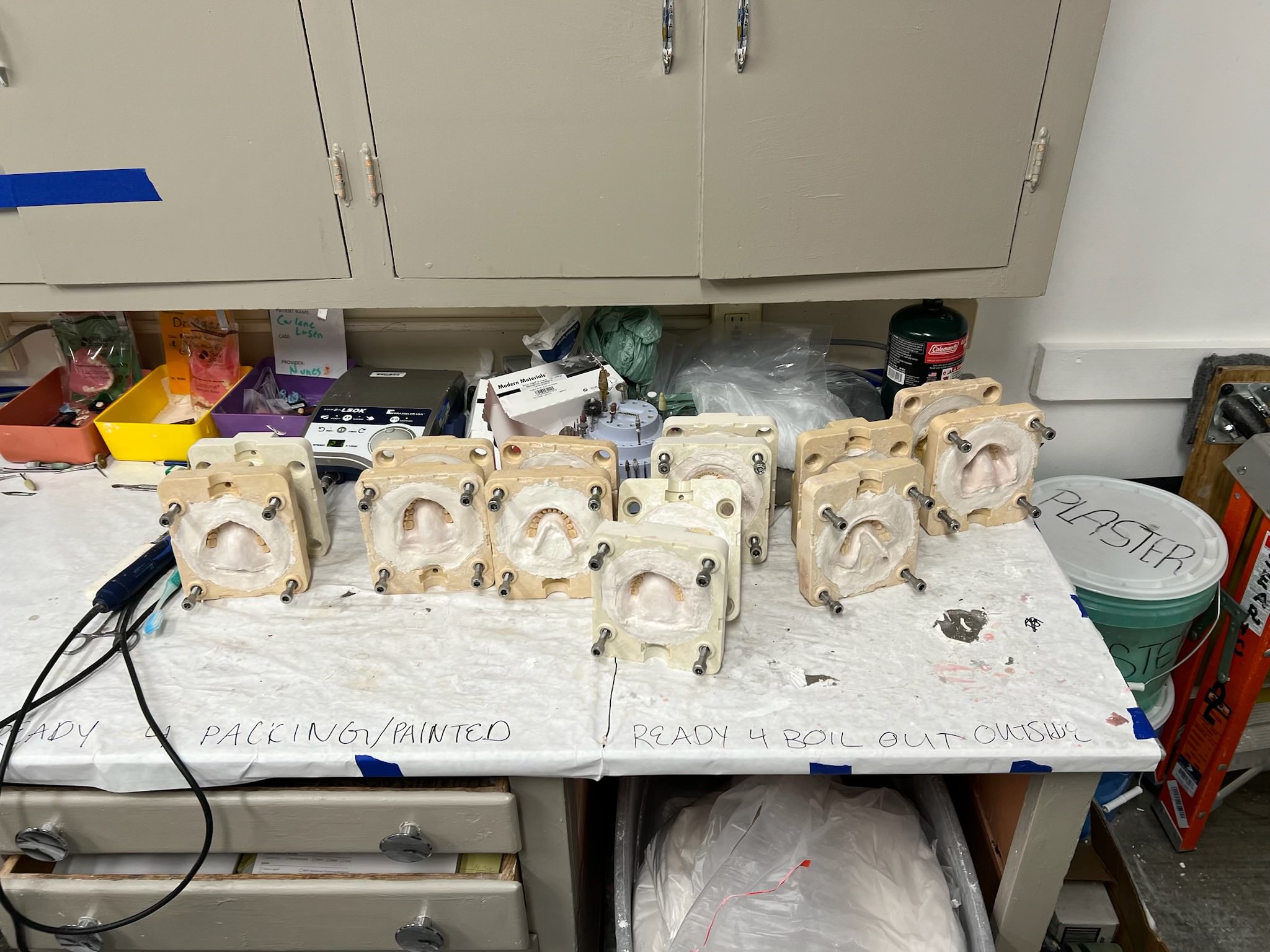

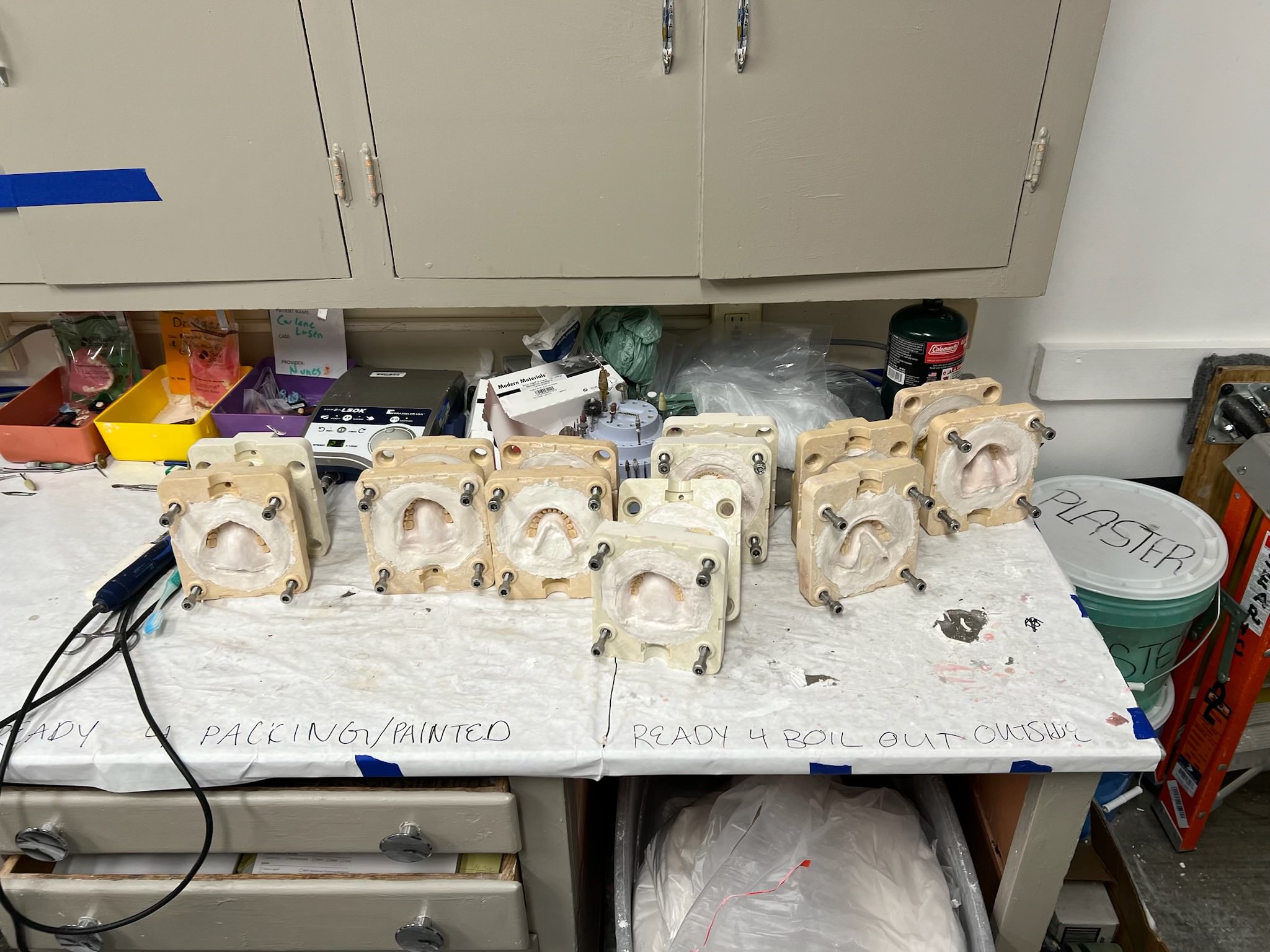

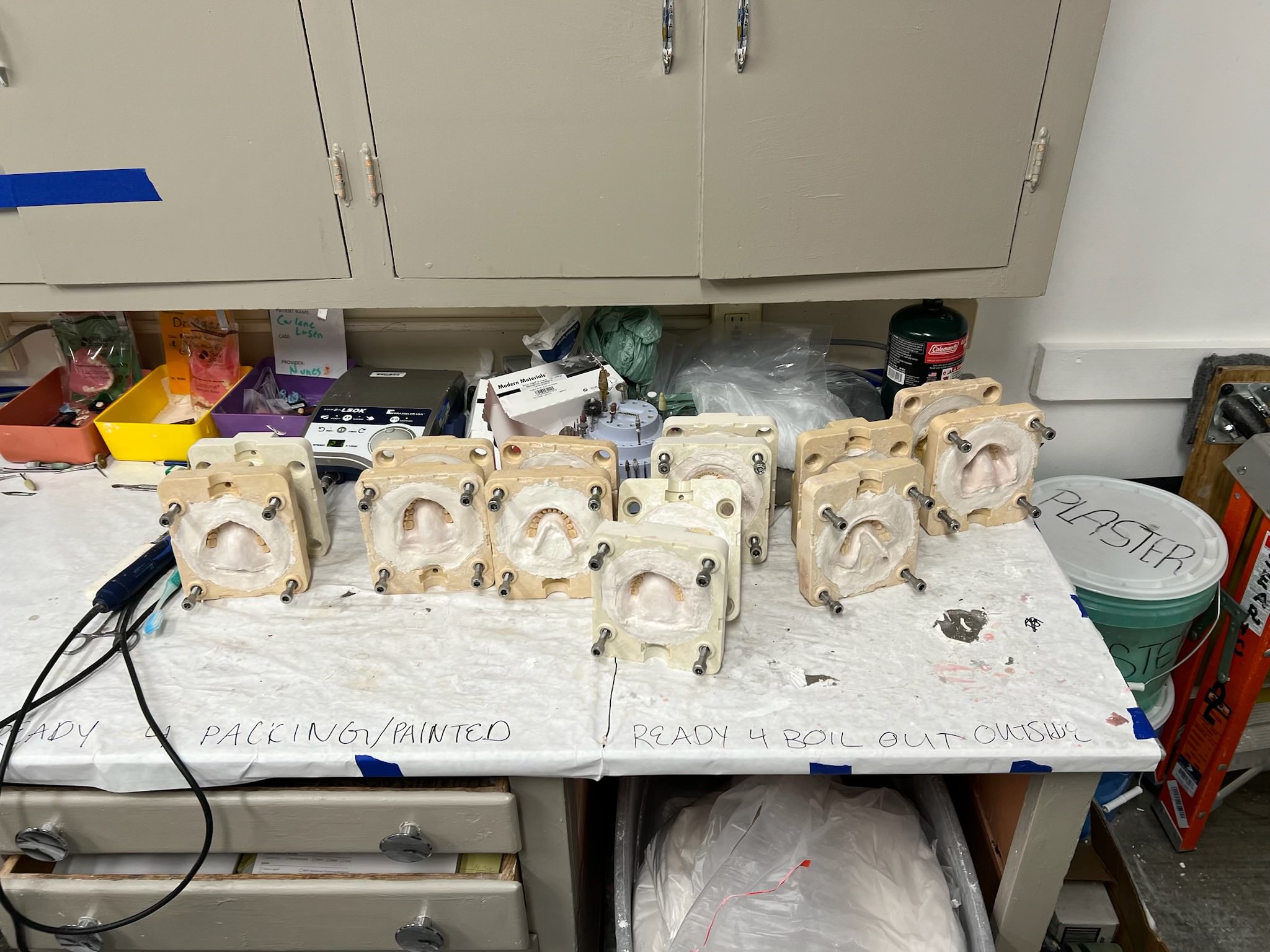

Using crab pots in a small burner — a far cry from state-of-the-art technology at home in Farmington — the UConn team uses the “boiling” method to make dentures. After examining the patient, a mold is created and the wax is poured into the mold. The wax is then heated and melted, forming the denture in the mold. The patient is visited several times after the initial fitting to ensure that the denture fits perfectly without pain or other problems.

“The fabrication of dentures is a process of at least four appointments. It’s very labor intensive and we don’t have the equipment we have in Farmington,” says Taylor. “People think we boil crabs, but we make dentures. It’s archaic, crude, but the result is incredible – the patients are very kind people and appreciate what we do.”

More than four decades ago, the Academy of Prosthodontics started a program in various parts of the country to provide dentures to underserved populations. In 1993, the program landed in Juneau, Alaska with an Oregon general dentist and Southeast Alaska Regional Health Consortium (SEARHC) member, Dr. Thomas Jordan, at the helm. In 1997, Taylor joined Jordan and in 2003 the clinic moved from Juneau to Sitka.

From the start of the program, Jordan meticulously handled all the logistics of organizing all the local patients and making sure they were able to get to the island and stay for the entire week. Jordan also follows up with patients as needed after the week ends. According to Agar, this is a huge undertaking.

“Logistics is a big problem — scheduling, organizing and lining up patients. If you have problems, you only have that week to do it and every minute counts. We have to be at a certain stage at a certain time,” explains Agar.

Jordan is retiring this year after 31 years of running the program, which means this summer was likely the last for the program that helped transform the smiles of hundreds of Native Americans. There is no designated successor and no one locally is willing to take on massive responsibility.

Understandably, this is bittersweet for Taylor and Agar. While they are sad to see the program end, they are filled with countless memories of the people who have helped along the way.

Taylor fondly remembers a patient who had a bite so disjointed, he asked if his jaw was broken. “He said, ‘Yes! You’re the first dentist to ask me that.”

“We made him the ugliest set of dentures and he absolutely loved them,” Taylor recalls. “He went out and ate a steak the first night – which we advised him not to do – and came back the next morning saying how much he loved them, he was in no pain. He was so grateful.”

Each year, Taylor and Agar bring in a team of 3-4 prosthetics residents who have just completed their second year of residency, and another clinician who is also an Academy member with SEARHC and the Academy of Prosthetics who foots the entire bill. . The trip is a big hit among the residents, as they always return and — very excited — share their experience with incoming residents.

Not being able to take residents to Alaska is one of the toughest parts of the program ending, according to Taylor and Agar. It has become an expectation and everyone is looking forward to the trip once they start their stay at UConn.

Dr. Audrey Brigham, a second-year resident, was part of the last group to return a few weeks ago.

“It was an absolute honor to be part of the final group of UConn Prosthodontics residents selected to represent our program at a rural hospital in Sitka, Alaska to volunteer to build dentures for people in need,” says Brigham. “Throughout the process, residents learned the importance of adaptability and patient-centered care, gaining valuable insight into the unique dental needs of rural populations.”

On Brigham, the experience will leave a lasting impression as she continues her career as a prosthetist.

“Participating in this voluntary outreach program has been a transformative experience for both physicians and patients. For patients, many of whom had limited access to dental care, receiving custom dentures was a life-changing event, greatly improving their quality of life and self-esteem. For resident physicians, the program provided a rare opportunity to apply their specialized skills in a real-world setting, fostering professional development and a deeper appreciation for community service.”

Brigham continues, “This once-in-a-lifetime experience highlighted the profound impact dental care has on individual lives and highlighted the critical need for continued volunteer efforts in underserved areas. I am beyond grateful to have had the opportunity to participate in this outreach program – and I cannot emphasize enough the absolute impact the experience has on every resident who attends.”

When asked if there are any plans to ever return to Sitka, especially after spending a week every summer for nearly three decades working tirelessly to deliver an average of 30 dentures per trip, Taylor and Agar looked at each other and smiled.

“Yeah, we’re planning a fishing trip,” Taylor remarked.